Of the many politicians I follow online, no one communicates as clearly and effectively as the Lithuanian Minister of Foreign Affairs (MFA) Gabrielius Landsbergis. I started following him with interest during the diplomatic tensions between Lithuania and China in 2021; the appreciation was mutual, as he also retweeted some of my memes; this fact particularly impressed my Lithuanian friends, even those that didn’t vote for his party: “He is cool, his whole family is cool”.

Reading more about him, I discovered the important role that the Landsbergis played in Lithuania history over the last centuries. And as I am a curious person, I decided to direct-message him and ask if he would agree to an interview. “Labas! That would be interesting, set it up with my advisor, she’s a fan of yours”. I thought this conversation could be interesting for DG MEME’s readers too, just as a reminder that the EU has a lot to offer, besides Macron, Von der Leyen and Sánchez.

Here I am, in Vilnius, walking down the corridors of the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Lithuania. I am accompanied by Eglė, an old friend from my Erasmus days in Austria, who was so kind to support me in my research work. Gabrielius Landsbergis welcomes us with a gentle smile. He is quite tall (taller than Dombrovskis!), has a firm handshake and piercing eyes. He shows us his office, describes a few memorabilia of his diplomatic trips, and then the interview begins.

How was it to grow up in the Landsbergis Family?

Like any other family, I suppose. When you’re little, you don’t see the whole, wide political pictures, it’s just a family like the others, with parents who are loving and caring but also busy. It’s only when you get a bit older, as a teenager, that you figure out who is sitting in front of you at the dinner table.

Was there a particular moment, as a child, when you realized the role of your family, and specifically of your grandfather, for Lithuania’s history?

I would say when we reached independence, in 1990, when I was eight years old. I had seen meetings in my kitchen, in which some people that looked very important were discussing things that I did not understand. Then the first democratic elections came and then March 11 [On that day the Supreme Council elected Vytautas Landsbergis as its chairman and formally declared the re-establishment of Lithuanian independence, ed]. I connected the dots and it became obvious: “That’s my granddad over there, saying this speech”.

As a child, I had seen meetings in my kitchen, in which some people that looked very important were discussing things that I did not understand.

The Nineties, a period of great uncertainty for the Baltic States. How was the atmosphere at home?

Quite tense, especially during the January events [a series of violent confrontations between the civilian population of Lithuania, supporting the recently acquired independence, and the Soviet Armed Forces, ed]. I remember, it was between my birthday, which is on January 7, and my brother’s birthday, which is on January 13; my granddad visited me at home and he said: “It’s possible that this is the last time we see each other. Something bad might happen in Lithuania”, so he knew about the attack. And then I did not see him for a very long time, at least four months [His grandfather lived and worked in the Parliament, which was guarded by Lithuanian citizens, afraid that it could be stormed by the Soviet Army, ed]. The next time I saw him, I was allowed to go to the Parliament. And I baked cookies for him at home.

It was right after my birthday, I was nine. My granddad visited me at home and he said: “It’s possible that this is the last time we see each other. Something bad might happen in Lithuania.”

Thinking about your grandfather in those difficult days, what inspired you the most?

His stance. I mean, he was criticized for quite a lot of things that I am criticized for today. He taught me to just do the things that you believe you need to do.

“We can take an institutional photo in front of my Star Wars poster, I can never propose this to other guests”

“Fine with me, I have the same poster in my living room!”

Your job is surely very stressful, were there any events in these last years that gave you a moment of satisfaction?

I had this position for almost four years and in this period almost everything revolved around the war against Ukraine. At the beginning of the war, Ukrainians had to face the horror of invasion, and they started resisting and winning, this was a beautiful moment that gave me so much hope. It made me realize that Russians are not invincible and we can push them back, fight them back. That was probably the greatest joy of my career.

Realizing that Russians are not invincible, that we can push them back, fight them back, was probably the greatest joy of my career.

In 1864 the Russian empire banned the use of Lithuanian language, but it survived thanks to the book smugglers (knygnešiaĩ), who kept printing and distributing copies of Lithuanian books using Latin characters. In the picture above Jurgis Bielinis (1846–1918), nicknamed the King of Book Smugglers.

I see you have a big poster of Star Wars in your office, do you quote it a lot?

[chuckles] The right amount of times, I would say. I recently read Our Enemies Will Vanish by Wall Street Journal’s Yaroslav Trofimov, a wonderful reportage of the Ukrainian refusal to surrender. So I wrote to the author that I really liked his book: “It’s like watching Star Wars’ A New Hope, when anything seems possible. And now that the war is stalling, we’re watching The Empire Strikes Back. And the third movie is in the making”.

Let’s hope it’s “Return of the Jedi” and not “1984”. Besides the Star Wars quote, I really like your communication style and your tweets, they’re clear and always to the point. Do you receive criticism from senior diplomats accusing you of being too direct?

No, I wouldn’t say so, I never received explicit criticism for something that I said or wrote. Me and my team, we put a lot of effort in choosing the right words to convey our point of view without crossing a certain line. Also I think that for a country as small as mine, it is imperative to be heard very clearly. Because in these hard times muddling our messages might be existentially harmful.

In these hard times muddling our messages might be existentially harmful

And when you meet the other Minister of Foreign Affairs in Brussels, do you feel they understand the point of view of Baltic states? What is the hardest thing that you have to explain them?

History. And for us Lithuanians it is hard to understand that history is not understood. Almost every family in Lithuania either has or knows people who have been deported during Soviet times. My wife’s grandparents were all out. My grandmother was also deported. I tell her story, in meetings or in conferences, and people are shocked: “No way, really? How could it be?”

And I tell them, as a child I remember that in 1990 the Soviet organized a military parade, with the same tanks, the T-72, that Russia currently deployed in Ukraine. And in 1991 they were attacking the Parliament and the TV Tower. Western people know all this, they acknowledged it, but they think: “It’s in the past, history is over”. But for Baltic people history is still there, it’s not in the books, it is part of our personal memory.

You have been recently added to the “List of enemies of the Russian Federation”. You jokingly thanked your family for that, but how does it make you feel?

I think in my original tweet I wrote: “I want to thank the academy”. In general, all the threats that Russians make to Baltic politicians are taken as an encouragement, it means we’re doing something right.

Some countries, like Estonia, are discussing introducing laws that could affect Russian minorities living in the EU, like limiting the usage of Russian language or their right to vote. What do you think of these measures, are they wise?

For us the situation is a bit different than in Estonia, so it might be difficult for me to comment on their policies. In our case, we have a very limited Russian minority in Lithuania, though we have related problems: our Parliament is debating what to do with the Belarusians who are coming to Lithuania every year. But they are migrants, they are not a minority which belongs to the country. Still, hearing too much Russian in the streets, which reminds us the dark days of the Soviet occupation, it affects the way people think; and this influences the political debate, because politicians feel that they have to solve this problem somehow.

Therefore, I would not be totally surprised if the Parliament passes some sort of restrictions for Russians entering Lithuania. There is this sensitivity and I understand where it’s coming from, though I don’t necessarily agree with all the decisions of our Parliament. Even our Prime Minister had to go out and tell people that Russian language is not the problem, that they should not feel offended by it; it’s just good people simply speaking their language. But since the war started citizens are way more sensitive to it.

Our Prime Minister had to go out and tell our people that Russian language is not the problem, that they should not feel offended by it; it’s just good people simply speaking their language. But since the war started citizens are way more sensitive to it.

Lithuania will soon be celebrating twenty years in the EU very soon, what is the biggest contribution that Lithuania brought to the European project?

Our main contribution was showing the world the transformational power of the EU. Look at the improvements, look at the results; and I am not just talking about the infrastructure, which is now great in Lithuania, but also about the cultural change and the fact that we successfully became part of the western geopolitical sphere. It is a victory for us but also for the EU because we showed that enlargement [the process of welcoming new countries in the EU, ed] is possible: we can do it and we should do it, look at Lithuania.

“A commonwealth of fifteen nations?”

[with a smile] “Not necessarily fifteen, perhaps twelve”

Vytautas Landsbergis diplomatic visit to the US looking for political protection from the Soviet Union (1990)

(1852–1916)

His relatives participated in the failed Uprising of 1863 against the Russian Empire, negatively impacting the family wealth. He attended the Šiauliai Gymnasium where he started learning Lithuanian. In 1884, his house became a gathering place for many Lithuanian intellectuals. He was forced to leave Lithuania in 1894 and later imprisoned and sent in exile to Smolensk. He returned in 1904, and he started working at the first Lithuanian newspaper. In his last years he wrote and directed many plays, one of which was adapted into Birutė, the first Lithuanian opera play.

He added Žemkalnis to his surname, which is a direct translation of the German Landberg (Land Mountain) to Lithuanian.

So you’re in favor of further enlargement, with the Balkans for example?

Look, accession is always merit-based, it was for us: we had to undergo grueling reform, the same for Latvia and Estonia. We had to really implement all the requests and requirements that were put on the table. I remember it well, because that’s when I started working as a diplomat, just before we joined the EU. This whole building where we are now was an anthill of people running around and implementing this and that regulation, and figuring things out that were incredibly difficult. It was just a decade after we got our freedom back. And we had to process this gazillion of documents and implement all of it. [with passion] And we did it and it is working! So I’m very much in favor of merit-based accession. Europe can do it and the candidate countries can do it, if they want to.

This whole building where we are now was an anthill of people running around and implementing all the EU accession requirements. And we did it and it is working! So I’m very much in favor of merit-based accession.

(1893 – 1993)

He studied in Vilnius and taught math in Riga. In 1918 he fought in the Lithuanian Wars of Independence: against Bolshevik forces, against the pro-German military formation of the Bermontians, and against Poland. After WWI he moved to Rome where he studied architecture. He returned to Lithuania in 1926 and became a successful architect in Kaunas. He became the minister of infrastructure in the short-lived Provisional Government of Lithuania, which tried to keep Lithuania independent both from Soviet and Nazi occupation. In 1949, he emigrated to Australia and worked in Melbourne. In 1959, he returned to Kaunas in Soviet Lithuania and worked as architect and restorer of monuments until retirement in 1984.

Why would you say the Baltics succeeded in both a cultural and economic transformation, while other countries that I will not name, like Hungary or Slovakia, did not?

Well, I wouldn’t say they did not succeed. What they are going through now is a phase.

A phase? This sounds optimistic…

We are watching and we’re concerned, obviously. I’ve said that about Hungary, it feels sometimes that its government is against Europe, and we are ideologically on different sides. I am pro-European, I want Europe to be stronger, to enlarge and offer support to those who need it. And the government of Hungary is against Europe as an idea, they want to see it dismantled. This is unfortunate, but Hungary is culturally ingrained in the European fabric, just think of their literature, their poetry and their long, painful history, which was significant already in the Middle age.

Her father was the linguist Jonas Jablonskis. During WWI, she studied and worked as a doctor in Petrograd, Soviet Union. She returned to Lithuania in 1921, working at the Red Cross Hospital in Kaunas, becoming the first woman heading the department of ophthalmology. She was named Righteous Among the Nations for saving and hiding Jewish people escaping the Holocaust.

Yet, seeing their staunch pro-Russian support, it seems that Hungarian people, or at least their government, had a different confrontation with their past than the Baltic States? After all, Goulash Communism made Hungary the happiest country of the Eastern Bloc.

From outside it is difficult to understand the narrative that connects the government, the people, their history and their outlook to the future. But now we’re seeing thousands of citizens going out in the streets of Budapest, demanding something different. It is complicated but I have faith that this is a phase.

You were an MEP for two years in Brussels, how did it go?

For me it was an extremely interesting experience, even though, as a young MEP, it was not easy to figure out how things work there. When I started my mandate, the first war against Ukraine broke out, Crimea had just been attacked and then occupied. And I was in charge for the EU-Russia report.

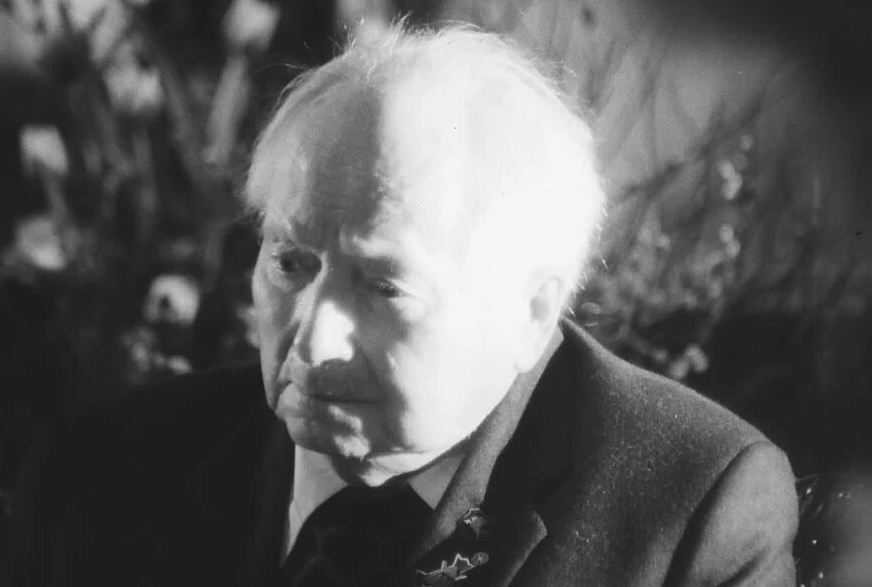

(1932, 92 years old)

Musicologist, pianist, chess master, book writer, Chairman of the Restoration Government, and former MEP. Vytautas entered politics in 1988, co-founding and leading the opposition party Sąjūdis (“Movement”). Thanks to this, Lithuania was the first Baltic state to declare its independence from the Soviet Union. Landsbergis served as Speaker of the Seimas from 1996 until 2000. He ran, although unsuccessfully, for president in 1997.

As a young MEP, it was not easy to figure out how things work in Brussels

That’s when they refused you entry to Moscow, right?

Exactly, that was my first badge of honor. Anyway, my report was about geopolitics, and I was mostly saying the same thing that I’m saying today. Time didn’t make me very original.

There have been some spats between the Lithuanian President and the Government, which culminated in the appointment of the new Defense minister. Any chance to resolve these internal divisions, which are quite dangerous during a war?

That’s how democracy works, there’s no other way around. I’m telling you what I’m telling myself: it could be worse. Our electoral system is structured in a way that the President, who has the popular mandate, often has to criticize the government to maintain his popularity. He has not so much power to implement what people expect from him, so criticism is the only way for him to remain relevant.

(1930 – 2020)

Lithuanian pianist and pedagogue, second wife of Vytautas and grandmother of Gabrielius. She was exiled to Irkutsk, Siberia, from 1949 to 1957. After returning to Vilnius she became concertmaster of the Lithuanian Opera and Ballet Theatre.

Our electoral system is structured in a way that the President, who has the popular mandate, often has to criticize the government to maintain his popularity.

This institutional friction is not only with our government, it happened already in the past. And about the risks for security, I can tell you that there is in the end a deep agreement on what needs to be done, even if this is not shown openly to the press.

(1962, 61 y/o)

Writer, journalist, director of films and theater, children’s book writer. He holds a degree in Lithuanian language and literature. He studied film-making in Tbilisi, New York and Warsaw. He has five children; Gabrielius, the oldest, is the only child from his first wife.

You and Commissioner Sinkevičius reached important political roles when you were still very young. Would you say Lithuanians are in general open to young people? I ask because in Italy if you’re not at least forty, nobody takes you seriously.

[laughs] After all you Italians invented the word “Senator”, adaptation of the word “Senior” which means old, so you have to keep up with this tradition. I must say, when we sit in the meetings you would see many young people from our delegations. I never really thought about that, but the same happens in Estonia. The fact that our politics started on one specific day is probably one reason for that: we had a generation of politicians that started with the Independence and now, after thirty years, they are leaving, opening up positions for young people.

We had a generation of politicians that started all together with the Independence and now, after thirty years, they are leaving, opening up positions for young people.

(1982, 42 years old)

Born in Vilnius, he studied History and International Relations. He worked in the Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in the Chancellery of the President and in the embassy in Belgium and Luxembourg. He was a MEP between 2014 and 2016, serving in the International Trade committee and in the Security and Defence sub-committee. He ranks among the wealthiest members of the Seimas, primarily due to his wife’s chain of private schools and kindergartens. He has four children.

A few more family questions, if you don’t mind.

Sure.

Reading about the Landsbergis is like reading a history book: you can trace your ancestors back a thousand years. What is the oldest document in your family?

One of the daughters of my great-grandfather remained in Australia when her father came back to Lithuania but she was very interested in our history and she traveled everywhere to trace our family’s lineage. The oldest document she found mentioning the Landsbergis was from the 12th Century.

I suppose it was written in German?

Yes, we came to Lithuania as a unit in the 16th century.

You come from generations of troublemakers [the Minister laughs]: already your great-great-grandfather was fighting against the Russian Empire in the 19th Century. And yet from what I read about your father, he doesn’t seem to be much involved in politics, does your political passion come from your grandfather then?

All my relatives from my father’s side were also involved in architecture and humanities. The first troublemaker that you mentioned was into opera and wrote the first opera in Lithuanian. My father also developed his humanistic side to the extreme, and became a writer. But he is also a public person, who expresses opinions; and he even writes jokes on Facebook!

Getting in touch with another culture also means exploring their humor and memes. In Lithuania there is an old myth from 90s that is still quite popular: “Vytautas Landsbergis stole all the Šiferis (eternit)”. Back then, Lithuanian economy was in dire conditions, also because the country had to privatize its agricultural sector. Some people managed to adapt to this radical change, some others did not. The latter blamed Landsbergis for dismantling the Kolūkis (Kolkhoz, the collective farm system) and spread the rumors that he was selling the eternit of the farms’ roofs.

This is used as a metaphor by Landsbergis supporters: he took away something that people were really attached to (eternit and collective farming) and which was toxic to them (like the asbestos contained in the eternit or the forced “union” with Soviet Russia).

By the way, doing this research I discovered that eternit is a Belgian invention!

Your great-grandfather Vytautas moved to Australia after WWII. How did he manage, with his personal history of partisan of the First Lithuanian Independence, to come back in 1959 to Lithuania SSR? Did he have any diplomatic protection?

Not really. In those years, the Soviet institutions were trying to bring back as many people as they could and used that for propaganda: “The life in the West is so bad that people are returning to the Soviet Union”. Quite a few Lithuanians chose to come back, even from the US, genuinely believing that life here would not be very different from when they left. My great-grandfather’s just wanted to reunite with his family: he returned with one son, Gabrielius, to meet with his younger son Vytautas who remained in Europe.

Most of your ancestors are named either Vytautas or Gabrielius. Is this some kind of family tradition?

[laughs] A bit, but it’s not a strong tradition: none of my children is called Vytautas, even though my first child’s second name is Gabrielius.

Your father’s name is Vytautas V. Landsbergis? What does the V. stands for, we didn’t find this on any book or interview, is it a secret?

[chuckles] Oh, it’s an old family secret. His name is the same as my grandfather’s; and also the same as my great grandfather’s. So to make a distinction he just added that V, the second Vytautas.

[Advisor: “You have time for one last question”]

How do you think the war is going to end, is Putin going to die in his bed?

How Putin ends his rule is for the Russian people to decide. What matters is that we go back to the internationally recognized borders of Russia. We want to reclaim all the territory of Ukraine, giving it back to the people and their elected government; this is our role. What happens in Russia it’s up to the Russian people. We shouldn’t be helping, assisting, or worrying. It’s up to them, it’s their country and they have to deal with it.

How Putin ends his rule is for the Russian people to decide. What matters is that we go back to the internationally recognized borders of Russia.

A big thank to Eglė, Agnė and Konstantinas, for the incredible support, the laughs, the wonderful conversations, the tireless translations, the detailed explanations and the Vilnius tour; to Anna, for changing my complicate to complicated; and to all the photographers I stole the pictures from: I hope you’re fine with that, otherwise let me know.