At Colours of Ostrava, one of Czechia’s biggest culture and music festivals, I had the pleasure to meet and interview Martin Dvořák, the Czech Minister of EU affairs over a Czech beer and Belgian fries. As a passionate traveler, I couldn’t miss the opportunity to ask him about his life and his many missions abroad.

You were born in 1956 in Prague, were also your parents originally from the capital?

Yes, they were. When they got married they lived together with my grandparents. The apartment eventually became too small and they decided to move to Pardubice, a town a hundred kilometers east of Prague.

Was it is easy to move to other towns in Communist Czechoslovakia or did you need permissions from the Party?

It was relatively easy, as long as they considered you a “good guy”. It was not as strict as in the Soviet Union.

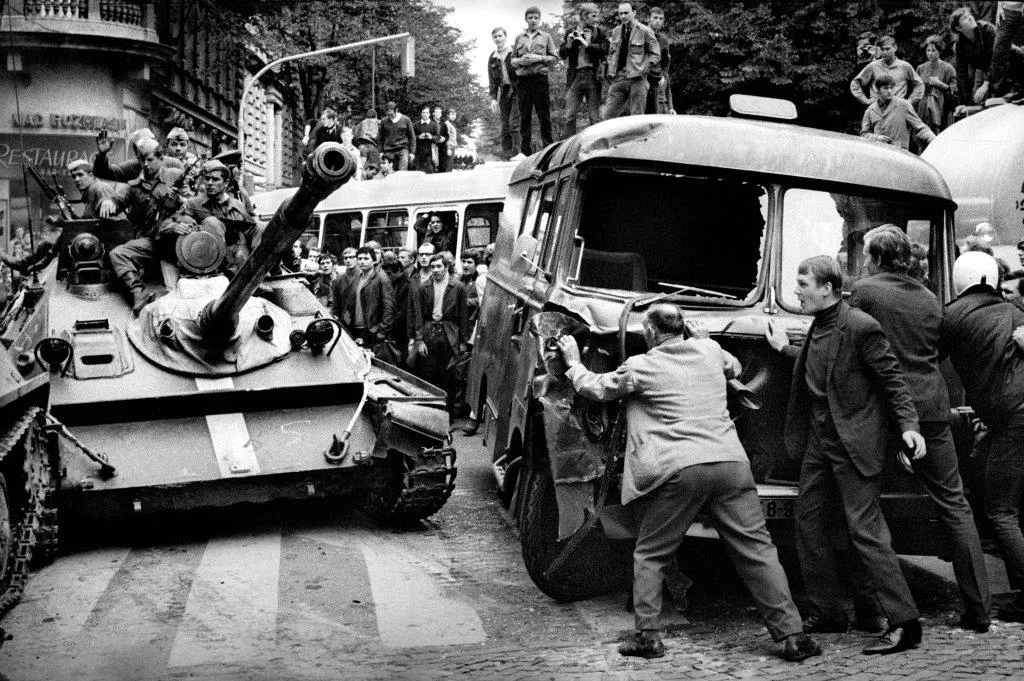

You were twelve years old during the Prague Spring, what do you remember of those days?

We were not in Prague in those days, it was the 21st of August 1968, we were in the countryside. I remember my father woke up my mom saying: “We have been occupied!” and my mother asked him: “By whom? The Americans?”

On 21 of August 1968 my father woke up my mom saying: “We have been occupied!” and my mother asked him: “By the Americans?”

Moscow’s violent reaction against Dubček’s liberalization attempts came completely unexpected?

Yeah, absolutely. And on that day my brother, who was nineteen, left the cottage where we were staying because he had some examination in Prague. We were really afraid, we had no way to know what happened to him. Finally, after two days, he came back and he told us what he saw: tanks, soldiers, dead bodies, destroyed buildings… I was just twelve but it is a very strong memory.

Did this experience impact your perception of the world?

Yes, it was very formative, because since that I hate Russia, and I was always afraid of meeting somebody with a Russian uniform. At that age, you have just perceive things in black and white, there’s bad and there’s good.

How was the time after the Prague Spring, when the control from Moscow became even more oppressive?

They were difficult years, I had the feeling that they were stealing a big part of my life, because we had no freedom anymore, no books, no theater, no cinema, nothing.

After the invasion, I had the feeling that the regime was stealing a big part of my life, because we had no freedom anymore, no books, no theater, no cinema, nothing.

How did your family react? Did they become dissidents or stayed quiet?

They surely did something to upset the regime, because both of my parents were expelled from their administration business. My father was sent to do manual labor and my mum had to change many positions.

This must be disruptive for a family with children…

My father felt very guilty towards us, because our life standards worsened. So he started to do private translations, from German to Czech and vice versa, using a fake name, so that the police would not find out it was him. He was working at night, to provide all he could to his family.

How come he spoke German?

His mum was a Jew from Prague, so she was fluent in German (and also French and Italian). So my father was raised bilingual, for him it was easy to translate.

Which side did your father take in World War II?

He was a member of the Communist party since 1944, he took his membership in the working camp of Benešov u Prahy, where he was imprisoned with his father. He managed to escape on May 5, 1945, when the Prague revolution started, and he fought on the barricades, he even got a medal for bravery. He was a convinced communist, but in 1948, when the communists took over Czechoslovakia, he disagreed with the party’s dependence on Moscow and decided to quit it. And that’s how his troubles started.

Not an easy background, close to be marked as enemy of the people…

In fact we were not allowed to travel abroad and also getting an education was difficult. My brother was expelled from university, because he did a hunger strike, asking the Russian army to leave.

Following Jan Palach’s example?

Definitely, Palach was a strong inspiration for him, but fortunately he decided to take the slower path of hunger strike, in the hope to get a reaction. He didn’t succeed, of course, the Russians didn’t move. And after that he was expelled, they sent him to work to a power plant.

Palach was a twenty-years old Czech student who set himself on fire in 1969 to protest against the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia.

For westerners it is hard to understand how ideals that inspired people all over the world could create a system that was rotten to the core. Was there anything good in it, something that we lost in our modern society?

Personally, I was young, that’s what I miss the most of that period. But I would say for the majority of people, that inhuman system offered security: they didn’t work too much, they didn’t work too hard, they didn’t get too much money, and they didn’t have to care about anything, because the Communist State was taking care of every aspect of your life: school, work, holidays… You had no obligation nor possibility to decide. I still think that freedom is more important than security, but many people that grew up in that system miss the latter today.

For the majority of people, that inhuman system offered security: the Communist State was taking care of every aspect of your life, you had no obligation nor possibility to decide.

Finally, you got closer to the end of the nightmare: when did the protests in Czechoslovakia reach momentum and why?

At the beginning of 1989 you could feel that the change was close. Before that, I had one principle: “Never say publicly something you believe in”; this was a way to cope with the system: if you didn’t protest in the open, you could survive. Suddenly, I felt it was not enough, I had to speak loud when I didn’t agree, so I took part in the many protests against the government and the regime, including the so-called Palach Week, in January 1989. That was the time I was shortly jailed.

Did the Fall of the Berlin Wall have a significant impact on Czech protesters?

Without doubts, it showed us that we were going in the right direction. I remember one demonstration after the Berlin Wall fell, we started shouting “Poslední v Evropě!” (“We are the last ones in Europe”, ed.). This slogan expressed the opposition to the government’s policies and a strong desire for modernization, so that we could catch up with our European neighbors.

How were you informed about what was happening in the West?

Via Radio Free Europe and Voice of America, I was listening to them every morning.

If you didn’t protest in the open, you could survive in Socialist Czechoslovakia. Suddenly, I felt I had to speak loud when I didn’t agree, so I took part in the many protests against the regime

When did you have the feeling that you won the fight against Communism?

In December 1989, we had a gathering in a theater Hradec Králové, where I moved with my wife: a giant miner, he was at least two meters tall, goes on the stage and says: “People, great news, the Constitution has been changed, the Communist party is not ruling anymore”. There was a standing ovation of several minutes, and I will never forget that moment.

How did you get your first political position?

At the beginning of 1989, as a consequence of my involvement in the protests, I was sent to do manual labor in the same company I was working as accountant for. It was a small company, about a hundred people, and they all knew my face and my story. Colleagues would tell me: “We have to kick the communists out, you were against them even before 1989, you could be our leader”. I did co-found the local section of Civic Forum and I was chosen as responsible for economics. In that position I was proposed to become vice-president of the regional body in April 1990.

Was this the first elections?

No, there was no time for elections. These were the negotiations between the communists, who still had the formal power, and us, who were asking for the power. It was called “Round-table”, we were sitting together with the communists, some of them were able to communication and discuss, and we were pushing them to hand us over their positions. This already happened at national level, when the former Communist Parliament, under pressure from the protests in the streets, elected Vaclav Havel as President.

When was the first time you met Havel?

In Hradec Králové, when I was a mayor, I invited him to visit our city.

When did you have the first elections?

At the end of 1990, I was elected mayor for the first term and reconfirmed four years later.

You grew up in Pardubice, the rival city of Hradec Králové. How did an outsider from manage to pull that trick?

Many locals were impressed: “We’ve been here for generations and you manage to win”. The truth is, my wife, who was from that town, helped me to be less of an outsider.

Are there big differences between Pardubice and Hradec Králové?

Hradec is for sure more conservative, not very dynamic, everything takes a lot of time, but finally, when changes are made, they are persistent and structured. Pardubice is less traditional, there are people coming from everywhere, because back then there were new apartments and jobs.

So we reach 1998, how did you enter diplomacy?

In the elections of 1998 my party arrived second but the coalition against me was quite broad and I was not reconfirmed as mayor; just when I was thinking about my next steps, I received a job proposal from the Council of Europe, even if I had never been to Brussels nor Strasbourg.

Perfect timing, how did this happen?

As I had been responsible for a big regional center like Hradec Králové, I somehow ended up in a database of the Council of Europe. They were looking for somebody with experience in transitioning administrations from totalitarianism to democracy.

What was the destination?

Kosovo, I had to support the United Nation mission there. Initially the assignment was for six months, but I stayed more than two years.

The Council of Europe was looking for somebody with experience in transitioning administrations from totalitarianism to democracy for a mission in Kosovo. And I accepted.

What was your task there?

Establishing the city government of the city of Istog. In a way, it was a similar situation like Czechoslovakia: after the conflict the old power was gone and there was no legitimate entity to replace it. United Nations had the temporary control but we needed to involve the local population.

Which language were you speaking with them?

I had a language assistant, an Albanian guy who was also fluent in Serbian. His English was not perfect, so we negotiated in some kind of Esperanto. Somehow we understood each other.

So you had to trust that the interpreter not only communicates your words but also the spirit and the emotions behind it…

I am sure that many time he didn’t translate what I was saying, but he probably did it in my own interest.

Was is easy to make them accept your leadership?

The fact that I already faced similar problems, even if in a more familiar environment, helped me a lot. I was able to relate at a deeper level with the locals than my westerner colleagues, German, French, Italian, who didn’t have a direct experience with a totalitarian regime.

In such situation, what is the most important message to communicate?

It was vital to make it very clear that we didn’t come to destroy their traditions, that we were there to guide them not to rule them. Once this was accepted, we worked very well together.

What was the biggest challenge in creating a stable city council?

Making them decide who the leaders were. They already had political groups, but there was no clear voice, nor direction. There were long negotiations, every evening we were discussing; and drinking rakja.

Hard on the liver, for sure… Did you have to impose your point of view?

Just at the beginning: after many unfruitful individual meetings, I decided the composition of the council: two people from this side, three people from this, some from this ethnic minority and some from the other. All of them – all of them – told me: “This is not acceptable”. I told them: “I don’t need you to agree, this will be my decision, unless you make a proposal that you all agree upon. You have time until tomorrow “. They came within an hour and that was the moment when we finally started to work well together.

Were there many disappointing episodes?

Many. There was a very brave Serbian guy, the informal leader of this little village outside town. I visited him several times, I told him: “It would be great if you could come to the City Council and work with the others, because you have to live together. You will stay here for generations, they will stay here for generations”. He told me: “Yes, I will come for the meeting tomorrow” but he received a message from Belgrade saying that he was not allowed to do so.

Was there a moment you felt you got rid of the intoxicating consequences of violence?

A few times… Serbs were complaining: “We don’t have space for us, we cannot move through the village because they will kill us”. And Albanians were complaining: “You killed so many people in our village, we can’t just forget about it”. Then a driver joined the conversation and he said: “I was a father of seven children. When I returned home from fighting the Serbian soldiers, I found all my family killed: my wife, my children, my father. And I am here, sitting with you, trying to find a way to live together in the future. If I can do this, you also can”. In this moment I thought: “We are going to find a way to make it work”, but we didn’t.

This didn’t prevent you from working in other difficult situations, and I don’t mean Brussels… How did your journey to Iraq and Qatar continue?

The Czech minister of foreign affairs was building a group of experts for post-war affairs and surprisingly enough the leader of this group was an envoy I met in Kosovo a few times, and she was aware of my work there. So she contacted me, offering me a position in the group. I asked for two days to decide, but I knew after three minutes that I would have accepted.

What was your task in Iraq?

It was a short-term action of six months: I started in Bassora (today called Basra, ed.), trying to build, or rebuild, the local government. We also organized the first Donors’ conference for the reconstruction of Iraq, which took place in Madrid at the end of December 2003. During my stay in Madrid there was another outburst of violence in Iraq and I decided I had enough.

Kosovo was easier?

Yes, whatever we did, they loved us there. In Baghdad, whatever we did, they hated us; and it is not fun to risk your life if your work is not appreciated, so I decided to leave. My next mission was more relaxed and long term: I was appointed for four years as business councilor to the Czech Embassy in Washington D. C. As I was raising my small son, it was good to have some stability.

Finally, you returned to Europe?

Yes, I became a permanent member of Czech diplomacy and foreign minister Karel Schwarzenberg wanted to appoint me ambassador in Tirana. But to do that he needed the approval of President Václav Klaus, who who did not like me so much, and he refused to agree. So the minister decided to “punish” me and he sent me to the consulate general in New York instead. I stayed there for five years.

Why didn’t President Klaus like you?

Because of some spat during our first meeting. It was the beginning of the Nineties, he was minister of finance and the chairman of the conservative Civic Democratic Party (ODS), which just broke out from the Civic Forum. He was invited for some meeting in Hradec and, because of the fast-changing political landscape, I was also invited to attend, even if we were not in the same party anymore. We sat down and we started a tour-de-table. The first lady said: “Mr. President, I am not a member of ODS but I really support you”, more or less the same sentence that all the other people at the table said. So Klaus turned to his advisor and said: “Which kind of people did you bring to this meeting, I thought we were supposed to have a ODS meeting? Why should I listen to them?”. Then it was my turn and I said: “I understand I am here by mistake, I thought I was here to welcome the minister of finance as mayor of the city, I didn’t know it was a party meeting”. And I left. And he remember that, we met many time after that, and he still remembered that.

In the end, did you manage to get an ambassador position, after Klaus presidency?

Yes, after the New York mission I applied as ambassador to Kuwait and Qatar, it was supposed to be the last position of my career. In July 2021 I returned my diplomatic passport and retired. But a few months later they invited me to be the deputy minister of Foreign Affairs and almost two years later I was called to replace my friend Mikuláš Bek as minister of EU affairs.

Funny appointment, for somebody who never really worked in the EU…

Indeed. I always felt that everything that was EU was not really my business: so complicate, so many institutions, so much jargon. But already during the Czech Presidency, when I was deputy minister, I had the chance to learn more about the EU and its importance, especially after Russia invaded Ukraine.

I always felt that everything that was EU was not really my business: so complicate, so many institutions, so much jargon

What is your feeling when you go to Brussels? Is the whole thing working?

I sometimes feel like in Kafka’s Castle, and I still get lost in the corridors; but the more I learn about it the more it makes sense. It is the best option we have. And the EU has so many enemies that are out there trying to destroying it.

Why do you think this happens, for example in Czechia, which is a country that greatly benefits from the EU?

I already mentioned President Klaus, he was heavily opposing our EU membership, he refused to adopt Euro; and this is his heritage. Conservatives created this narrative of Brussels imposing things on us… They never mention the financial support or the fact that we can also shape decisions at EU level. It’s so easy to say that our problems are created by others.

Yet the Euroscepticism is well-rooted in Czech society…

Czech people have been ruled for three-hundred years by the Habsburgs, six years under Nazis, forty years under Soviets… We lost any trust in authorities and we are always looking for ways to bypass it. And we have the same approach towards Brussels.

In Brussels, I sometimes feel like in Kafka’s Castle, and I still get lost in the corridors; but the more I learn about it the more it makes sense. It is the best option we have.

Baltics States had a very similar history and yet their citizens are quite happy to be in the EU, even if they don’t really engage much in the EU elections. Why this difference?

I am a bit jealous of the Baltic States, because they avoided all the Euroscepticism that we have. Maybe they believe more in their own strength, maybe they understand the importance of the EU, because they know what is coming from Russia.

What do you think is the greatest contribution that the Czech Republic gave to the European Union?

What did we give?

Yes.

Maybe our Euroscepticism; and our humor. More seriously: I personally love it that EU politicians are still quoting Havel, who was a true European. And during our presidency we showed that we were able to find good solutions to unexpected problems such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I am really proud that the first politician who visited Ukraine a few days after the invasion was our Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jan Lipavský. And together with Poland and the Baltic States, we were able to convince the other countries that we had to stay together and support Ukraine.

I am really proud that the first politician who visited Ukraine a few days after the invasion was our Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jan Lipavský.

What was the hardest part of this moral suasion?

Cutting the connection to Russian energy sources and approving the sanctions. At the beginning France and Germany didn’t like the idea, because for them Russia is a very profitable market. Finally, we were able to persuade them that this was not the time to think only about profit.

Are you sure they are fully convinced?

Ok, I am not sure we really convinced Germany, but at least they were more open to discuss all these changes.

Last question: what did the EU give to the Czech Republic, beside money?

Ok, let’s pretend that billions of Czech Crowns are not so important. Freedom and peace, that’s what the EU gave us; not only the freedom of movement and trade, but also the freedom in our minds. In Czechia we have the first generation, those in their thirties, who were born, grew up and reached adulthood in a democracy. And let’s not forget that the Schuman Declaration was about peace, a reaction to the horrors of the Second World War: “Let’s try to find a way to negotiate without shooting each other”. And it’s working and we cannot afford to lose this.

Freedom and peace, that’s what the EU gave us; not only the freedom of movement and trade, but also the freedom in our minds.