UNICEF UNGA September 2022

© Tina Štrafela

It is with a certain apprehension that I follow the social media account of Janez Lenarčič, Commissioner for Crisis Management: I know that every time he tweets chances are there’s been a catastrophe somewhere in the world.

EU civil protection and humanitarian aid, which means responding to disasters and crises by coordinating assistance and funding, is one of the many EU responsibilities. It is particularly relevant in these days of climate emergencies and wars, so I was very pleased when the Commissioner agreed to an interview.

Tina Štrafela, his communications adviser, guides me to his office: he greets us with a quick look, pointing at the screen of his computer. He is listening attentively to the International Court of Justice’s interim ruling on genocide case against Israel. It is a historic moment, and the tension in the room reminds me of the final game of a world cup. “…orders Israel to take all measures within its power to prevent genocide in the…”, somebody must have scored a goal. Just the time to give a few indications to his assistants and the interview can start:

What can you tell us about the young Lenarčič, what was your dream job as a child?

I was dreaming of becoming a pianist: already before school my mother started taking me to concerts. Seeing those artists playing on big Steinway concert pianos, it was magic.

Concerts in Yugoslavia’s Ljubljana in the 70s, was it a very vibrant city?

Oh, yes, culture was, and still is, very big in Ljubljana.

What was your parents’ occupation?

My mother was an economist, and my father a small entrepreneur, I’d say it was a typical middle class family, even if we had a classless society back then.

Did you have a big family?

We are five brothers in total, I’m the second one.

Would you say having many brothers helped you developing diplomatic skills?

Definitively. For example, when we had to divide the house chores everybody wanted to mow the lawn, because that was fun, and nobody wanted to wash the dishes. It required some effort to find equitable solutions.

Was your family involved in politics?

My father was, though his involvement was limited to the socialist time, when we had only one party. He was very critical of the authority, especially of the socialist one, but also of those that came after.

Did his political engagement help you develop an interest in national politics?

Not particularly, I was always interested in foreign affairs, I wanted to work abroad.

What drove you in that direction?

I was an avid reader and I read many inspiring books about history and politics. Unfortunately I couldn’t follow my passion right away: if you wanted to work in diplomacy in socialist Yugoslavia you’d have to join the Communist Party and I didn’t want that. Eventually history turned my way and we became a democratic, independent country. So I jumped immediately on the first chance to enter the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

So, this was after the Ten Day War. Where were you during the conflict?

I was in Slovenia, I was just finishing law school when it started. I volunteered for the Slovenian Defense Forces. Despite the complex situation it was a good time because we were so optimistic and there was so much positive energy. There was an unprecedented high degree of unity among Slovenians and later on we never reached that again. But in summer 1991 we were like one.

There was an unprecedented high degree of unity among Slovenians and later on we never reached that again. But in summer 1991 we were like one.

What went wrong after that?

State Secretary for European Affairs Lenarčič and Prime Minister Janša during the Slovenian Presidency of the Council in 2008.

© Thierry Monasse/STA”

I think it’s normal that when you no longer have historic challenges in front of you and you can have a democratic life, you go back to the usual quarrels.

You witnessed Slovenia being born as a new country and you contributed significantly to its diplomacy. Was there a particular moment when you felt: “Ok, now we made it”

Yes, that moment was 18 July 1991, the day when an agreement was reached between the Slovenian Member of Federal Presidency Janez Drnovšek and the federal authorities, for the complete withdrawal of the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) from Slovenia. I was in the Slovenian Defense forces back then and I remember from that day onward I went to sleep without my gas mask and without my gun, thinking: “Now it’s done”.

From the 18 of July 1991 onward I went to sleep without my gas mask and without my gun, thinking: “Now it’s done, we are a nation”

Of course, our independence was not the final goal but just a necessary step on our way back to Europe. That’s why I would add two more significant dates: May 1992, when we became the 178th member state of the United Nations, recognized as equal by the other countries; and then spring 2004 when we finally made it to the EU and NATO, which was our historic goal. Since then, as we achieved everything we had in mind, we didn’t really know what else to want.

You were placed in a prominent political role by social-liberal, liberal and even Janez Janša’s right-wing government, who is very far from your views. How did you manage this? Is it enough to be very skilled or do you also have to pretend to be inoffensive?

You know, I didn’t ask for any of these positions, in each and every case they asked me to join their team. And I think this is good: at least in the past there was this notion that you need professionals to do the job and I wish this were still a regular practice in Slovenia; we are a small nation, you can’t replace everybody when the government changes.

Unfortunately there are increasing tendencies of selecting people based on their party affiliation and not on their competences.

Unfortunately there are increasing tendencies of selecting people based on their party affiliation and not on their competences. This is not good, we should nurture professional government services so we can use the best people we have all the time.

Talking about merit, you received a few distinctions yourself, from France (2008), Poland (2014) and Ukraine (2022). Any interesting story about them?

I appreciate any kind of distinction, but receiving the French Legion of Honour [Officier level, ed] was a very touching experience, perhaps because it was my first distinction and it is a very well known one. A founding EU member state awarded it to me, for my services to the European Union, immediately after my term as Slovenian State Secretary for European affairs. My mandate extended to the first Slovenian Council Presidency, after which we handed it over to France and they appreciated the hard work and intense cooperation.

I’m also very much honoured by the distinction given to me by President Zelenskyy for my role in supporting Ukraine in its fight for freedom and independence.

Moving to your current post, how was it to find yourself facing the pandemic of the century a few months after being appointed commissioner?

I certainly didn’t expect that I would have such an intensive mandate. I would have preferred less work, not because I don’t want to work, but because when I have work it means there are crises.

With all these complex decisions to take do you ever feel helpless or discomforted?

Not really, because, with very few exceptions, we are able to help. We are too busy organizing and coordinating our response to feel powerless.

What are these exceptions?

One occasion when we could not coordinate assistance was at the beginning of the pandemic, when Italy was asking for masks. There was no response because nobody had masks. We were not prepared because nobody expected another pandemic, and the last one we faced was the Spanish flu in 1918. So Italy was hit first and asked for help and in the meanwhile the virus spread all over Europe and we realized with horror that there were no masks.

How was this unexpected problem solved?

Our system is based on mutual solidarity, like in a village: one house is on fire and then we organize all the neighbors from other houses and we put down the fire. That is the philosophy of civil protection. But we realized that this was not enough if all the houses are on fire, we need some other resources to help. So already in March 2020 we started building the European strategic reserve (rescEU), precisely for cases in which some or even all the EU countries would be affected at the same time, without being able to help each other.

What is this reserve made of?

We have fire-fighting airplanes and helicopters, masks, ventilators, medicine, shelter capacity, generators and also chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear capacity.

The EU Treaties did not allow this response to be coordinated at European level: civil protection is a member state competence

Why didn’t we have this reserve before the pandemic?

February 2021, © Tina Štrafela

The EU Treaties did not allow this response to be coordinated at European level: civil protection is a member state competence. We needed member states to give us the permission to organize the efforts. Back then all we had were twelve fire-fighting aircraft.

The phone rings.

“Sorry, I have to take this, it’s Borrell”

“Ehm, should I… leave?”

“No, no”

I appreciate the transparency and the unique occasion to witness how the response and communication following the ruling is discussed between the Commissioner and the High Representative: “Let’s communicate it together with the Commission, it gives added weight if we do it together, so we don’t have different nuances, you know? EU unity!”

The phone call ends. “Sorry for the interruption, let’s continue”.

With all the tension of these days, do you manage to fall asleep easily?

Yes, because by the time I reach my bed I am usually very tired. The more tired you are, the better you sleep.

What is your secret to cope with all the stress?

What can I say? It’s not a comfortable job I have but it is a rewarding job, because you feel you are doing something meaningful. And this is important for me. I need this feeling and I have it in this job.

It’s not a comfortable job I have but it is a rewarding job, because you feel you are doing something meaningful. And this is important for me.

Your job means so much to you that you are focused all the time and you don’t really perceive the tension and the stress?

No, of course I need to disconnect, from time to time. I love being surrounded by nature. Back in Slovenia my hobbies were cycling and mountains, here in Belgium it is only cycling, because it’s a bit difficult to find mountains. And I know Belgium is a densely populated country, but it still has a wonderful nature.

It’s great to find something beautiful in the place where we live. You lived in Ljubljana, New York, Warsaw, Vienna and Brussels… Do you still like travelling or did it become just a tiring part of your job?

I really enjoy flying, especially long flights, because that’s the only time when there are no phones: a plane is the only place where I can have some peace. And I am really worried: some airlines are considering introducing internet on their flights and I hope they won’t do that.

As there are no phones, a plane is the only place where I can have some peace

Do you keep track of all the countries you visited?

I remember each and every one of them but I don’t really keep track or count them.

Commending the pilots.

Madagascar, March 2023, © Tina Štrafela

What is the most curious food you ate while on a mission abroad?

More than the food I ate it was the one I didn’t eat: when we went to Central Asia with a group of ambassadors, one of the staff members who knew the area warned us that, as we were guests of honor, they might have offered us lamb’s eyes [most likely a variation of Kash, ed]. So we were kind of excited but unfortunately they didn’t offer us that dish, though the food was excellent.

As we’re already with food, we might as well discuss some big questions on humanitarian topics: do you think humanitarian health assistance should have precedence on international humanitarian law?

Health assistance is part of international humanitarian law and it’s part of our humanitarian action. We do not only provide food and water but we also provide funding for health services. It’s the international law, as you just heard from the ICJ, which says that there is a legal obligation for all parties involved in conflicts to allow and facilitate the provision of humanitarian aid. And this includes health assistance.

And should humanitarian help avoid impacting the local culture or should it try to shape it? I think of infant mortality, which is accepted as natural in several countries. Medications can help reducing it but if the local culture forbids contraceptives, the medical support will lead to extreme overpopulation (and thus poverty and migration), altering the existing balance.

Local cultures should be taken into consideration to the limit allowed by universal values: we don’t accept a local culture in which men beat their wives, because this is against universal values. But if in the local culture women must have their head covered, we should respect that. And we do provide funding for sexual and reproductive health services, but yes, we don’t really make a point about it.

Forbidding contraception is not against universal values, yet it can have dramatic consequences for many developing countries.

It is still unacceptable to let a newborn die when we could save them with vaccination: life has a value and has to be protected. As far as the number of children is concerned that is certainly the decision of every parent. There is a very strict correlation between the number of births and the empowerment of women through education and work. So if a country is worried about unsustainable birthrate there is a very simple recipe: get girls to school, get women to jobs and let them decide themselves.

So if a country is worried about unsustainable birthrate there is a very simple recipe: get girls to school, get women to job and let them decide themselves.

Chad, January 2024, © Tina Štrafela

Yet it took us centuries to understand that: we had to go through the medieval period (“God gave us Reason to understand the universe”), the scientific revolution (“Science works better than religion”), the suffragettes, the civil rights movement… How much time will it take until everybody embraces such complex cultural shifts?

I think it can happen in one generation: one hundred years ago an average family in Europe had ten children. Then in the sixties that fell to two or three, now we are around two.

About human rights: do you think they are enshrined in natural law (“Killing was always wrong, since the time of Cain and Abel”) or are they just a moral code produced by a very advanced society?

It is both, you know, these are the two schools in humanitarian law. I don’t think it really matters which of the two options one chooses, the only important thing is the evolving consensus on what human rights mean. The death penalty was practiced everywhere and now it is forbidden in most countries. The same goes with LGBT rights, a few decades ago they did not exist. So it is a process.

May I ask if you are a believer?

I am an agnostic, religion is something but I think we can’t possibly apprehend what that ultimate reality is.

Besides “doing the right thing” what would you say the EU gets back from the humanitarian support it offers?

What do we get back from humanitarian aid?

Absolutely nothing, that’s the point of it.

Absolutely nothing, that’s the point of humanitarian aid. In development aid you can make political, economic and security considerations. Humanitarian aid should be governed exclusively based on needs: there is somebody who needs help to survive or alleviate their suffering and you must help, expecting nothing in return.

Of course, if you are religious, you expect that in this way you will earn your place in heaven, fine. But in this world humanitarian aid is one way. Of course people say thank you but you should not demand or expect it.

Let’s move from global to local: Slovenia will soon celebrate 20 years by the EU. What is, in your opinion, the biggest contribution that Slovenia gave to the EU?

I think we gave Europe the understanding that the big enlargement did not bring some savages from the East, but countries and cultures that always belonged to Europe.

I think Slovenia gave Europe the understanding that the big enlargement did not bring some savages from the East, but countries and cultures that always belonged to Europe.

Did you feel you were treated unkindly during the accession negotiations?

Many politicians were afraid of this looming enlargement: “Nothing will work anymore, there will be no possibility to take decisions, we will get bankrupt because these countries are so poor”. I think Slovenians showed that we can perfectly work as well as other older EU member states. We were among the first to adopt the €, to enter Schengen and the very first new member state to hold the EU Council Presidency.

And what did Slovenia receive from the European Union?

The most important thing that Slovenia and any other member state get from the EU is the feeling of coming home, of having a seat at the family table, a sense of belonging.

Most Slovenians would start counting the money that came from cohesion funds of the EU budget to answer this question. I don’t, as I don’t think money is the most important thing. The most important thing that Slovenia and any other member state gets from the EU is the feeling of coming home, of having a seat at the family table, a sense of belonging. The Twentieth Century was particularly harsh on Slovenian people and in 1991 we felt liberated.

Look at this world, it’s getting crazier every day: the wars, the conflicts, climate change. Now imagine any of the EU countries being out there in this storm alone.

Look at this world, it’s getting crazier every day: the wars, the conflict, climate change. Now imagine any of the EU countries being out there in this storm alone.

If possible, would you like to keep your current post in the next Commission?

I’m really not thinking about that. Unlike some other colleagues, I’m almost sure I will be busy with this portfolio until my very last day.

Ahah, they should all do like you, instead of trying to jump here and there. Would you have any advice for your successor?

I don’t think I am in a position to give advice, because things change rapidly… But in general, if I were asked, I’d say: “It’s getting worse”. Even if, by divine intervention, all wars stopped today, even then, we are still in big trouble. Because we have already destroyed the climate and we can see that from our data: we have floods and fires with an intensity never recorded before. On the 6 of August 2023, on the very same day, we received two requests from help: one from Slovenia for floods and one from Cyprus for fires. “Dear successor, get ready for more troubles”.

To my successor I’d say: “Get ready for more troubles”

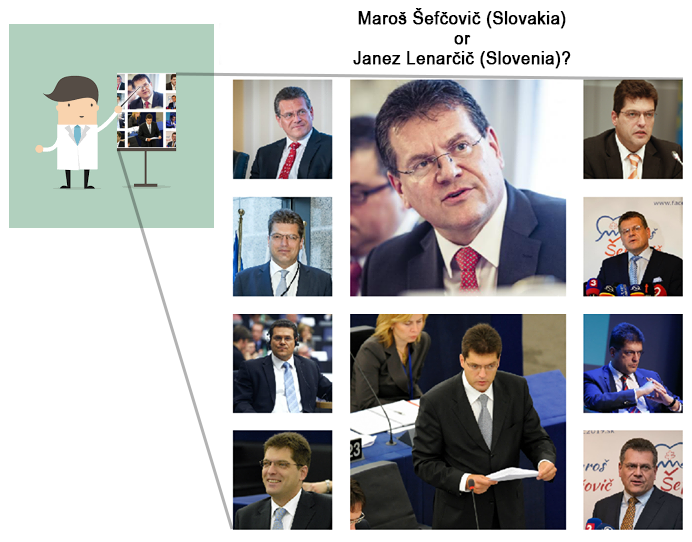

One last funny question: do people really mix up Slovenia and Slovakia? Did it ever happen to you?

Of course they do! It happens in many ways, I remember when we first joined the European table, before the accession. We took part in this Convention on the Future of Europe presided by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. And, according to the protocols, the name of the countries are in the local languages and we were seated in alphabetical order, so I was sitting next to my Slovak colleagues. And the guy who was chairing the meeting was looking at the nameplates completely lost: my nameplate read Slovenija and my colleague Slovensko. Even people that understand the difference between Slovenia and Slovakia could be confused by this. Or take the Commission’s Visitor Center: there you can choose the language, slovenščina or slovenčina, how can people distinguish that?

And I suppose it can’t help when * I flip my meme * even the two Slovenian and Slovak commissioners look similar. Thank you so much for your time!